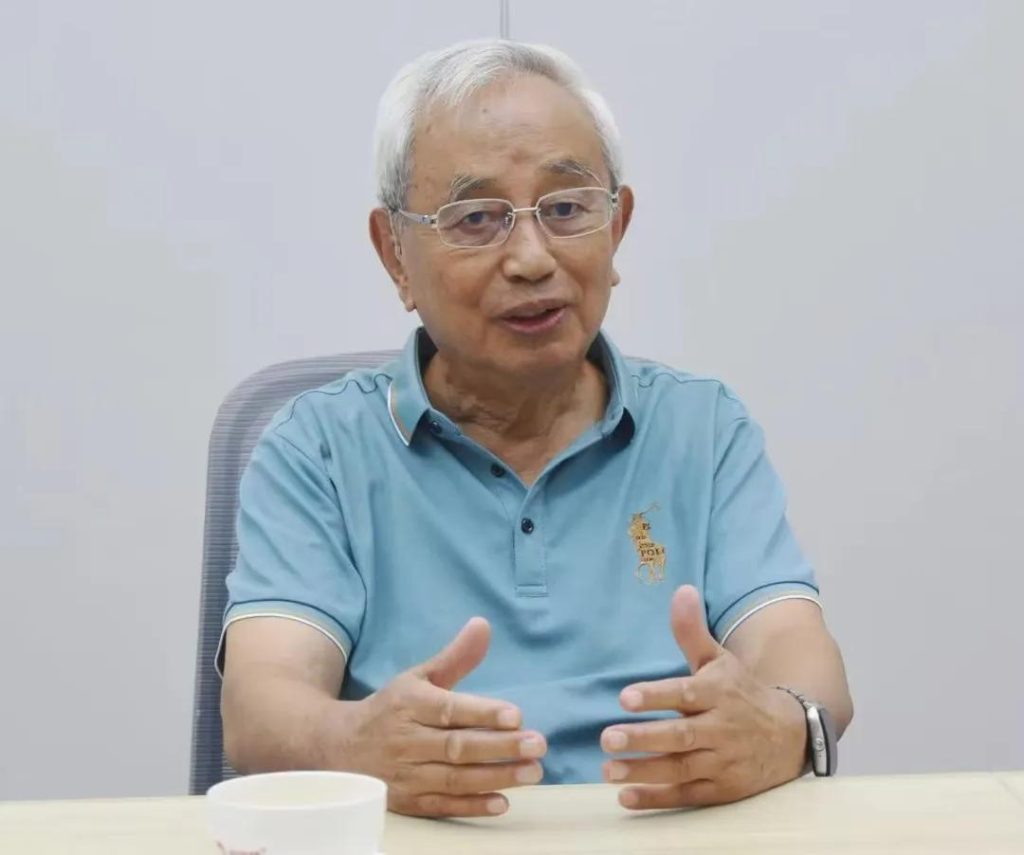

This article is compiled by Wu Tingyao from Professor Lin Zhibin’s keynote speech at the first Ganoderma Day Academic Forum in Fuzhou on July 6, 2024. After review by Professor Lin Zhibin, it was first published in the 103rd issue of Ganoderma magazine and is now reproduced here with the author’s consent. The photo shows the scene from the day of the speech. (Photograph by Wu Tingyao)

Have you ever considered that the “Ganoderma” we currently cultivate, study, produce, and use is primarily based on Ganoderma lucidum (red reishi), with Ganoderma sinense (purple reishi) as a secondary focus? Meanwhile, the black, green, white, and yellow Zhis recorded in the Shennong Materia Medica seem to have little relevance to us. Why is that?

The Shennong Materia Medica is the first monograph on traditional Chinese medicine that includes Ganoderma, compiled around the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty, over 2,200 years ago. It was not authored by a single individual but attributed to “Shennong” as a collection of folk medicinal experiences. The original text has long been lost, but its content can be glimpsed through citations in later works.

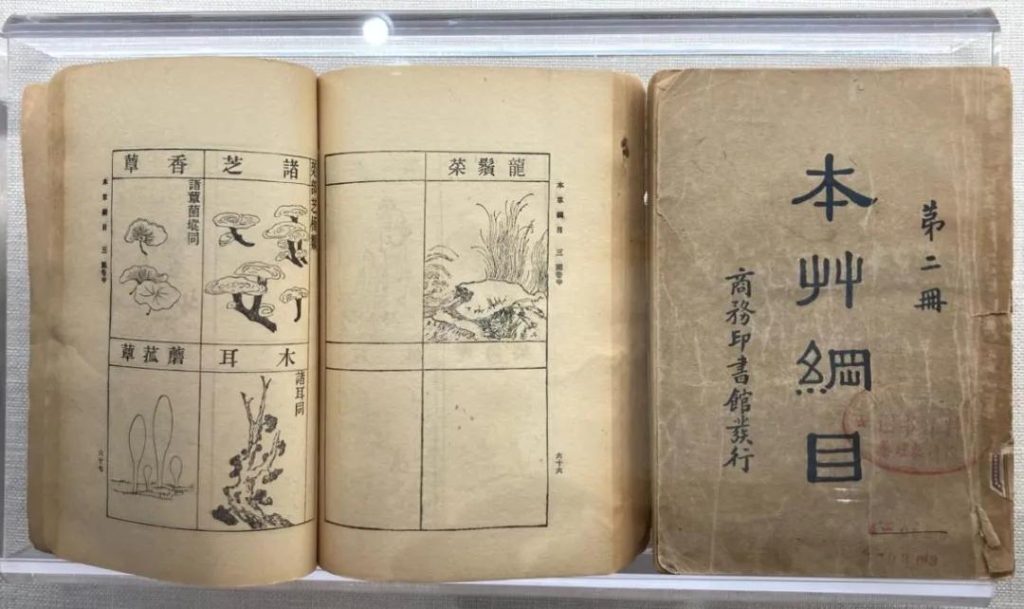

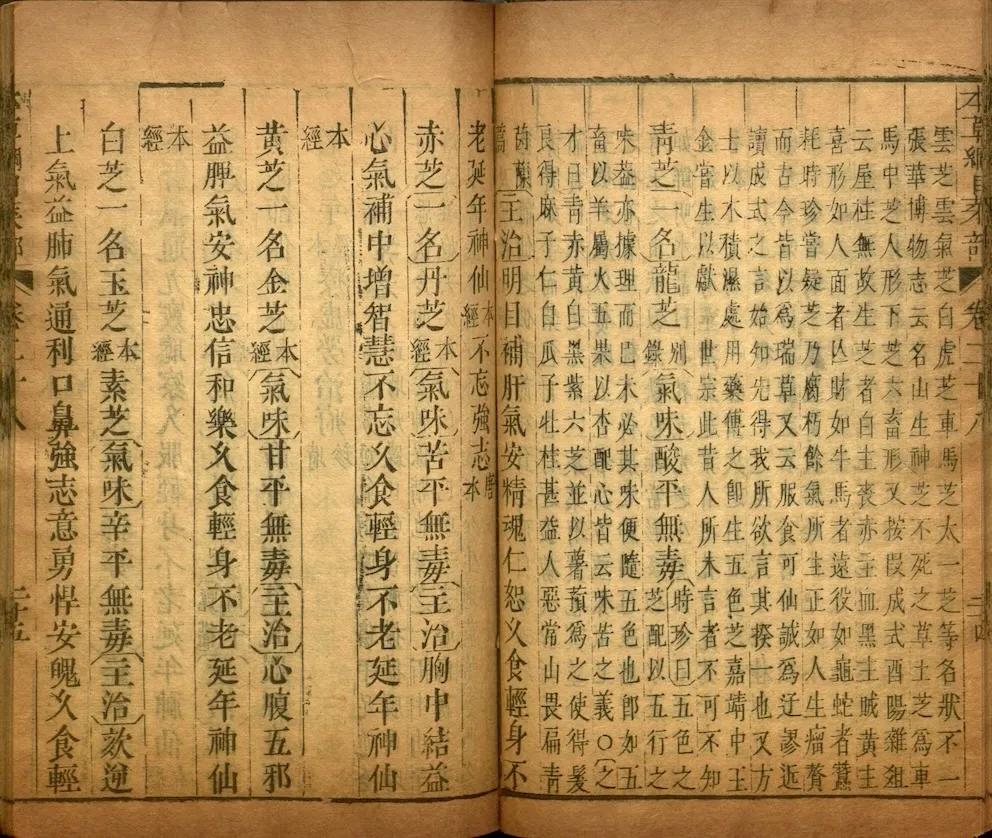

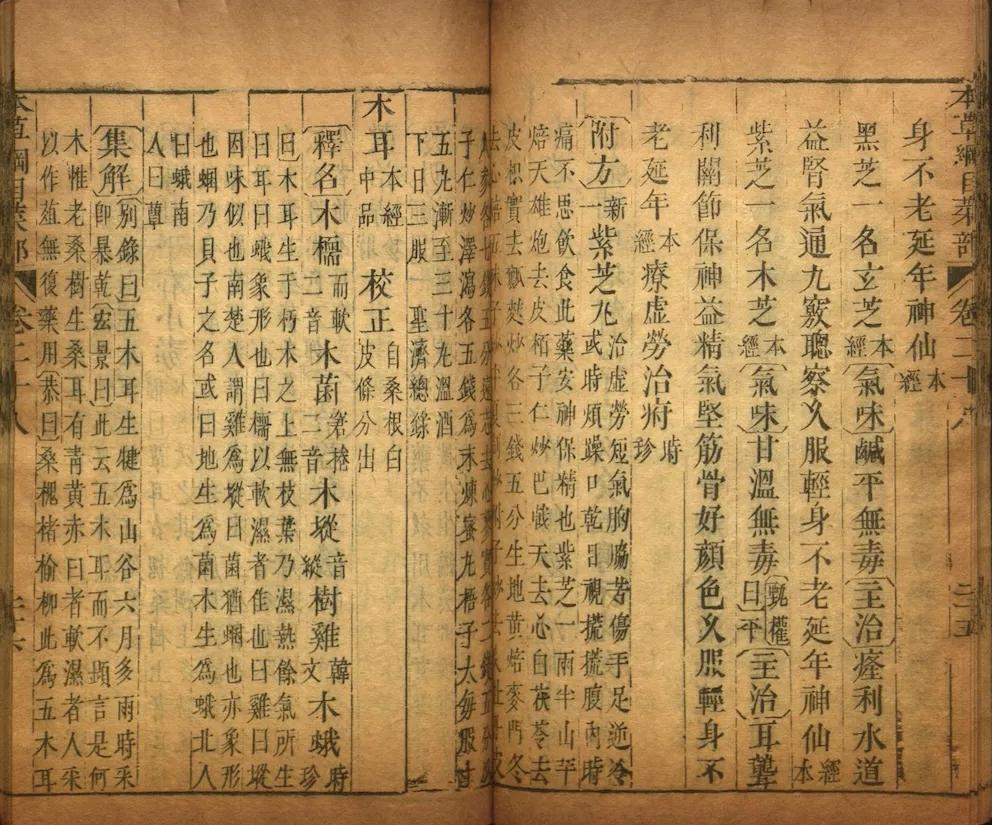

I initially encountered the discourse of Ganoderma in the Shennong Materia Medica indirectly through the Compendium of Materia Medica published by the Commercial Press about a century ago. Li Shizhen’s Compendium of Materia Medica was written during the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty, and it cites the original text of the Shennong Materia Medica verbatim, with only a few annotations. This means that the ancient discourse on Ganoderma has remained virtually unchanged for over 1,600 years.

The Compendium of Materia Medica collected by Professor Lin Zhibin is the version published by the Shanghai Commercial Press a century ago. The complete work consists of eight volumes and is currently on display at the “Professor Lin Zhibin’s Ganoderma Academic Achievements Hall” in Fuzhou, Fujian Province. (Photograph by Wu Tingyao)

Are all the “Six Zhis” actually Ganoderma?

In fact, the term “Lingzhi” does not appear in the Shennong Materia Medica. Instead, based on the theory of the five elements and five colors entering five internal organs in traditional Chinese medicine,

“Zhi” is categorized into five types: Cizhi (or Danzhi), Heizhi (or Xuanzhi), Qingzhi (or Longzhi), Baizhi (or Yuzhi), and Huangzhi (or Jinzhi), along with an additional type, Zizhi (or Muzhi). Each corresponds to specific therapeutic effects: benefiting heart qi, kidney qi, liver qi, lung qi, spleen qi, and essence qi. It emphasizes that all six types can promote longevity and keep one youthful with prolonged consumption[1].”

Aside from the Compendium of Materia Medica, the Newly Compiled Materia Medica compiled by Su Jing and others during the Tang Dynasty, as well as the Kaibao Materia Medica edited by Liu Han and others in the Song Dynasty, also largely quote the original text from the Shennong Materia Medica regarding the “Six Zhis,” with only minor annotations and no new content.

However, ancient classical texts of traditional Chinese medicine, such as The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic (Huangdi Neijing) , Treatise on Febrile Diseases, Synopsis of Golden Chamber (Jingui Yaolue), Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergency (Zhihou Beiji Fang), and Master Lei’s Discourse on Drug Processing (Leigong Paozhi Lun), do not mention the term “Zhi” at all. This indicates that the “Six Zhis,” which are highly regarded in Materia Medica literature, were not utilized in traditional Chinese medicine. As a result, research and application of Ganoderma saw virtually no development until the 1970s.

Some ancient scholars even held critical views regarding certain discussions in the Shennong Materia Medica. For instance, the Tang Dynasty pharmacologist Su Jing proposed differing opinions on the classification of Ganoderma’s growing regions based on the pairing of the “five colors” with the “five mountains.” He argued that although the text states, “Chizhi grows on Mount Huoshan, Heizhi on Mount Hengshan, Qingzhi on Mount Taishan, Baizhi on Mount Huashan, and Huangzhi on Mount Songshan,” in reality, “the Baizhi offered from various places may not necessarily come from Huashan, and Heizhi is not exclusively found on Mount Hengshan…”

Even Li Shizhen himself had differing opinions on the classification of Ganoderma’s flavors based on the five colors and five elements in the Shennong Materia Medica. He stated, “The five-colored Zhi, paired with the flavors of the five elements, is merely a theoretical concept; it does not necessarily mean that its flavor corresponds to its color [1].”

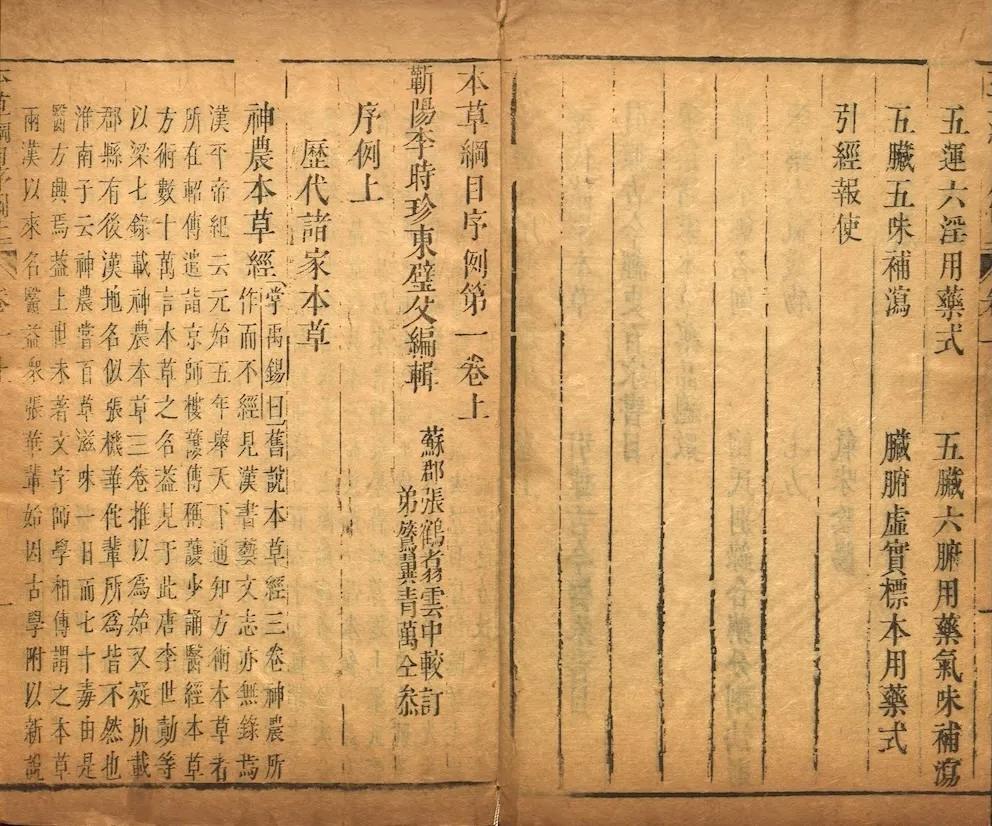

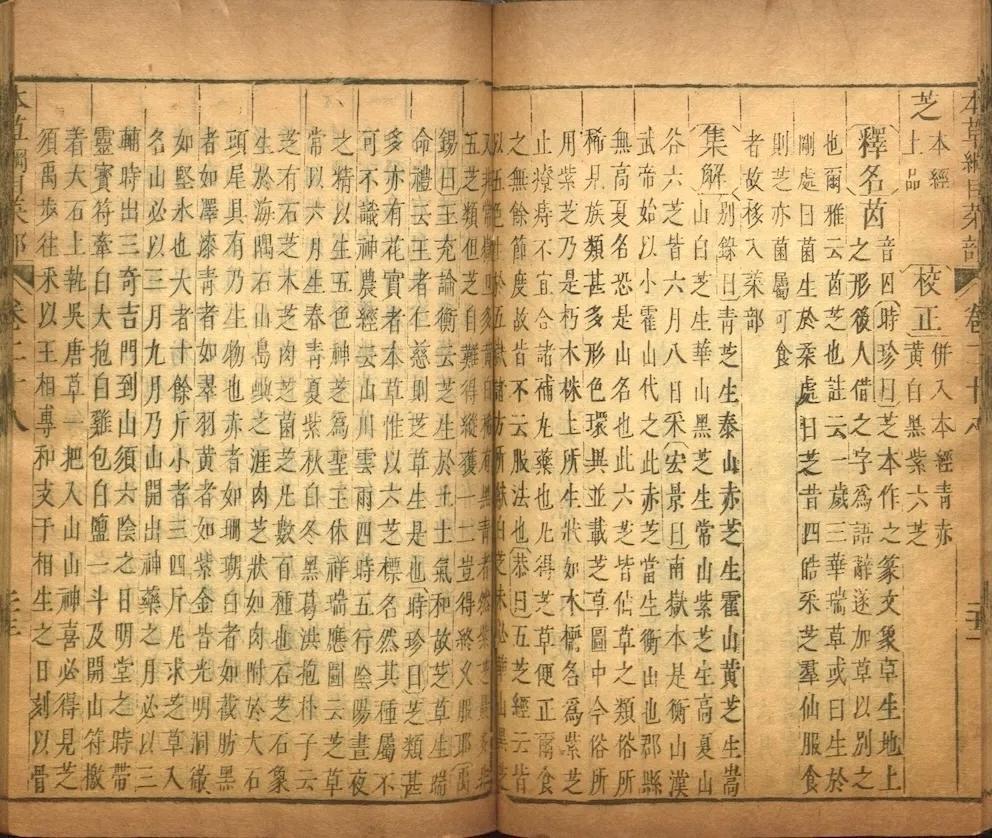

The Compendium of Materia Medica references the Shennong Materia Medica and the relevant pages discussing “zhi.” Li Shizhen’s annotation, “The five-colored zhi, paired with the flavors of the five elements, is merely a theoretical concept; it does not necessarily mean that its flavor corresponds to its color,” appears under the entry for Qingzhi. The version of the Compendium of Materia Medica shown in the image is a composite edition published in the 49th year of the Qianlong reign (1784), held in the Library of Congress.

Modern scientists also believe that the ancient term “zhi” should be understood as a general term for “mushroom.” Zhao Jiding, a contemporary mycologist who has invested significant effort in classifying Ganoderma, pointed out as early as 1989 that the “Six Zhis” described in the Shennong Materia Medica categorize “zhi” into six types, rather than indicating six distinct species of Ganoderma.

According to Mr. Zhao’s research, the term “Reishi” (Ganoderma lucidum) generally refers to the representative species of the fungus known as “Chizhi” in ancient texts. In modern biology, “Zizhi” corresponds to the species G. sinense. As for “Qingzhi,” “Huangzhi,” “Baizhi,” and “Heizhi,” they are likely not members of the Ganoderma genus but rather belong to other fungal groups[2].

In his 2023 work, Traditional Chinese Medicine scholar Wang Dequn pointed out that the “Chizhi,” “Qingzhi,” “Baizhi,” “Huangzhi,” and “Heizhi” mentioned in the Shennong Materia Medica are derived from later interpretations of the Five Elements and Five Tastes, as well as the correspondence between the Five Organs and Five Colors. These references relate to consumables rather than medicinal herbs, and they are clearly distinct from “Zizhi.” Therefore, it is concluded that they are spurious works attributed to alchemists, rather than authentic writings of Shennong, and should be deleted [3].

G. lucidum encompasses all the effects of the “Six Zhis”.

Since 2000, the only Ganoderma medicinal materials included in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China are the fruiting bodies of red Reishi (G. lucidum) and purple Reishi (G. sinense). They are explicitly noted to “enter the heart, lung, liver, and kidney meridians,” possessing the functions of “tonifying qi, calming the mind, and relieving cough and asthma,” primarily treating “restlessness, insomnia, palpitations, lung deficiency cough and wheezing, consumptive disease, shortness of breath, and loss of appetite”[4].

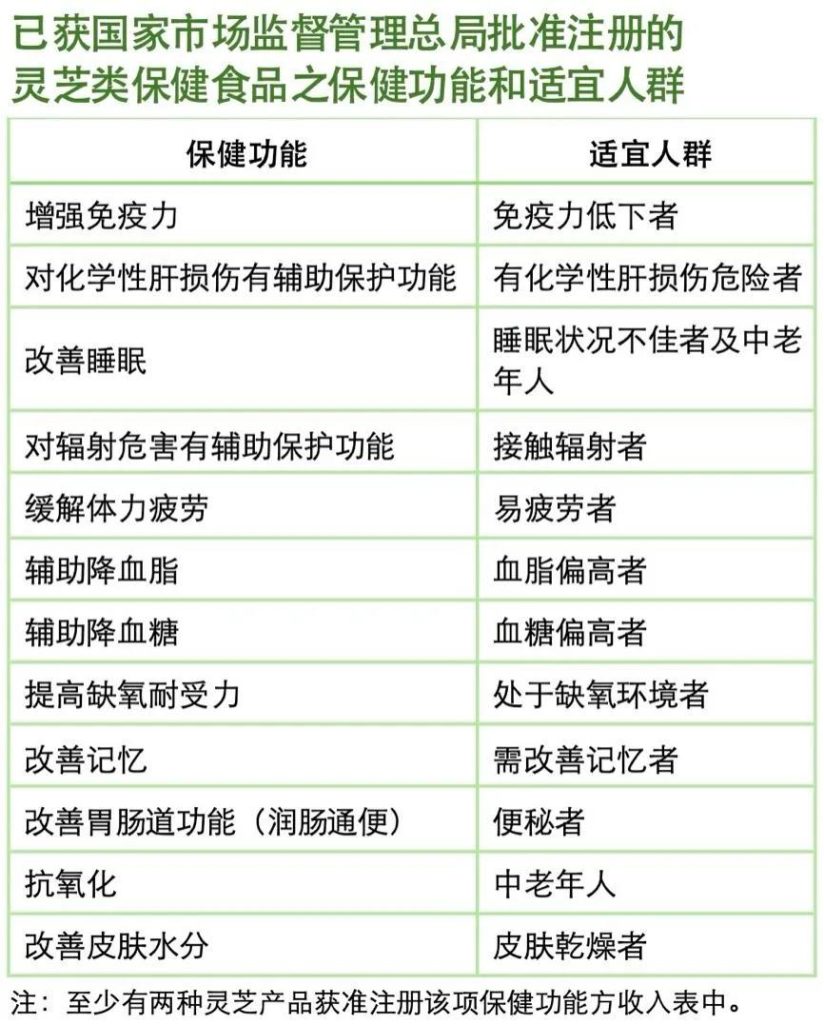

The Ganoderma species included in the “List of Fungal Strains Available for Health Food Use in China” comprise the aforementioned two species and G. tsugae. To date, these have accumulated more than 12 approved health functions as registered health food products with regulatory authorities (detailed in the table below).

Although the three aforementioned Reishi species have health benefits, the vast majority of scientifically discovered Reishi effects, as well as the Reishi products sold in the market and used by consumers, primarily come from the well-known G. lucidum. Since the 1970s, our research team has been guided by traditional Chinese medicine theories and clinical practices, employing modern technological methods to study the active ingredients, pharmacological effects, and mechanisms of action, with G. lucidum as the main focus.

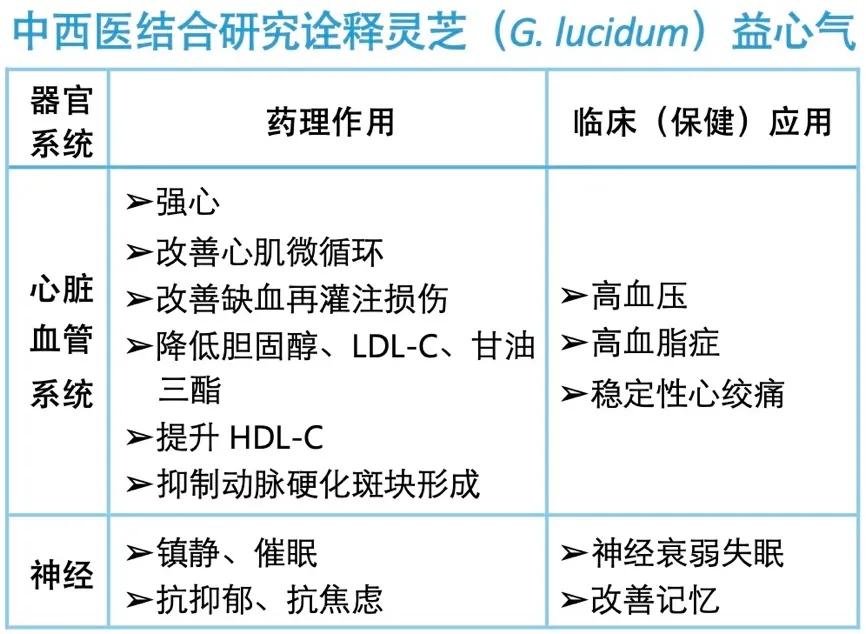

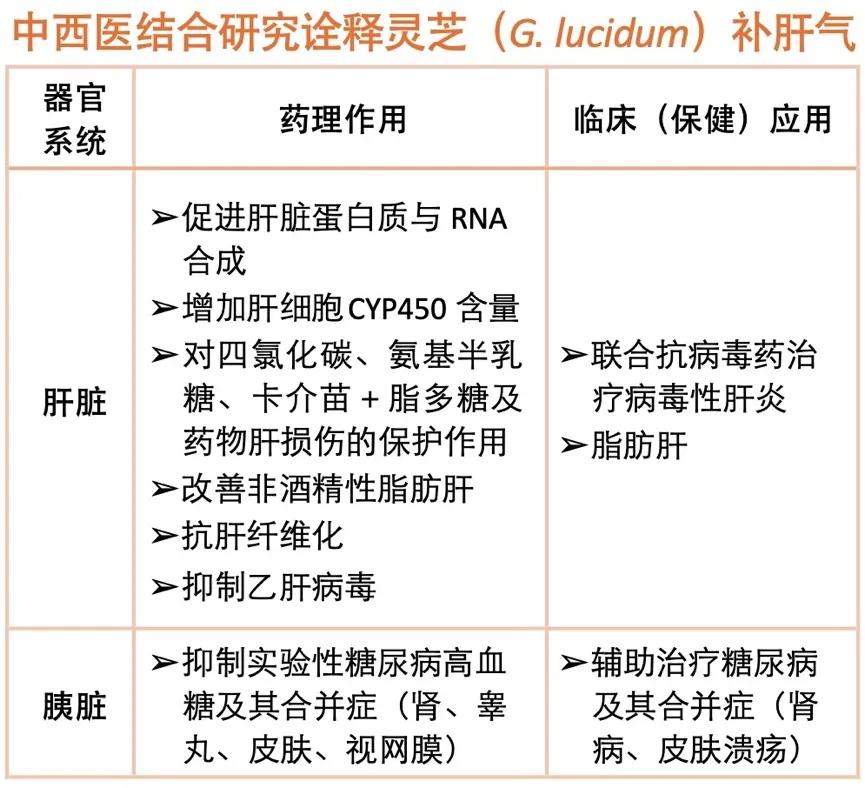

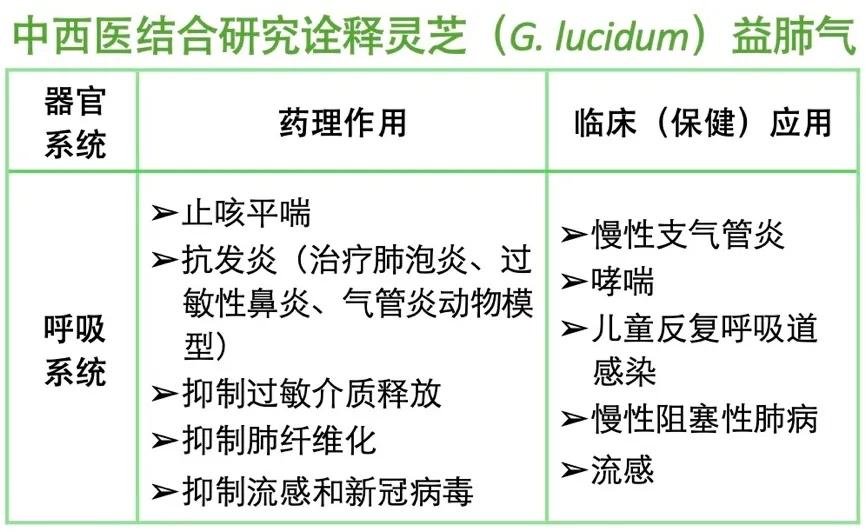

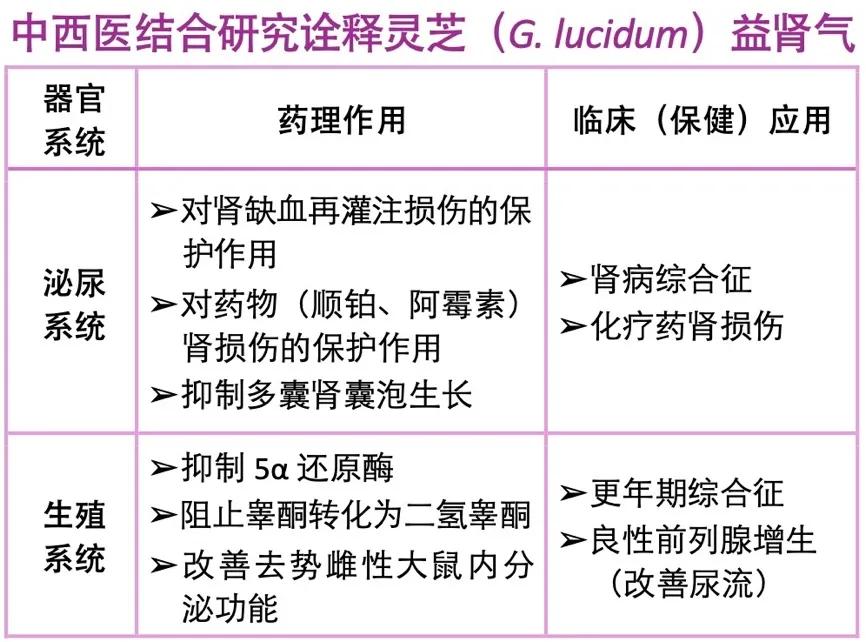

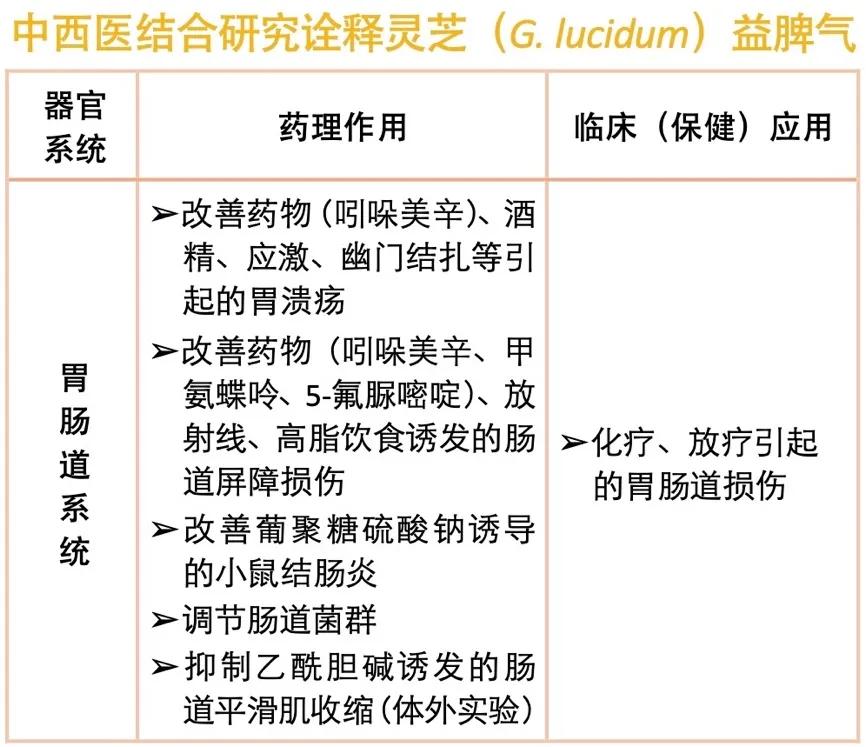

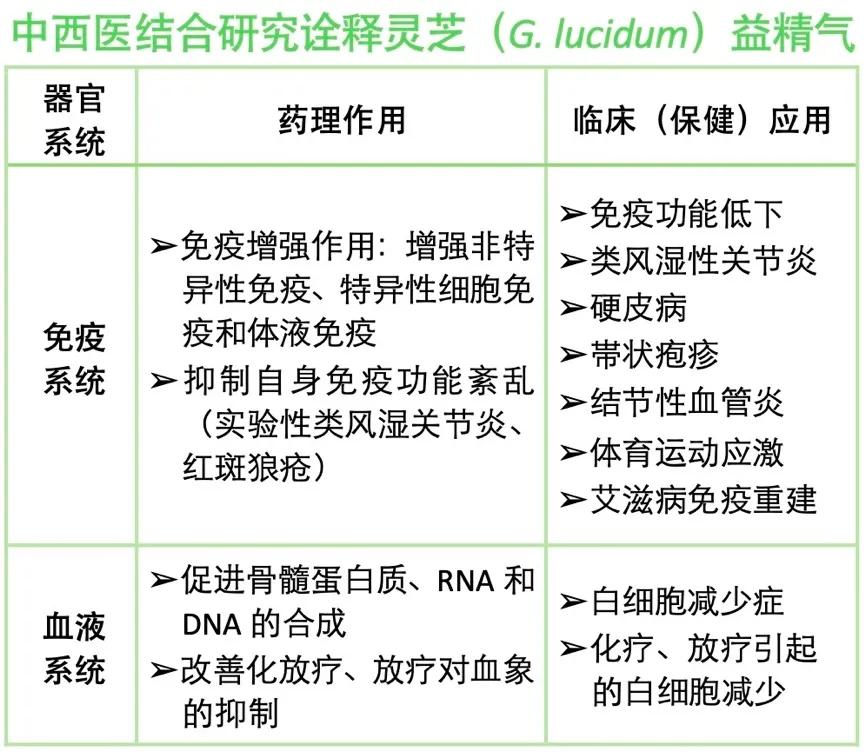

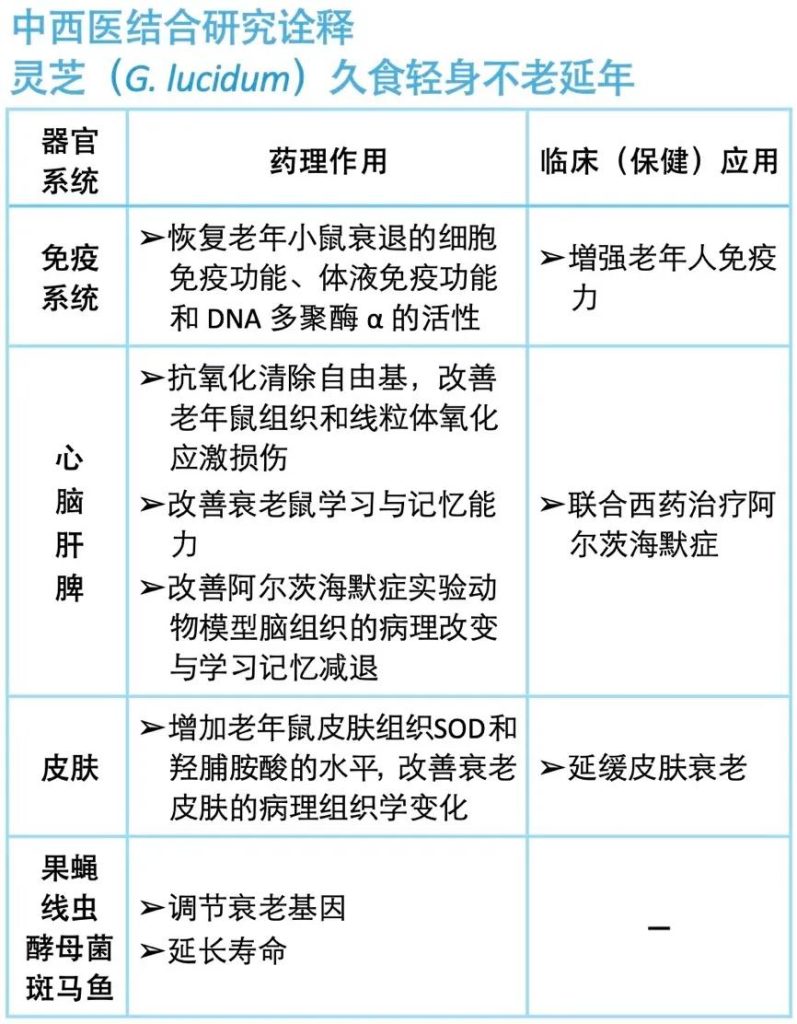

Comparing the results of 50 years of research on the pharmacological effects [5] and clinical applications of G. lucidum, alongside the health benefits of health foods made from G. lucidum, with the effects of the “Six Zhis” discussed in the Shennong Materia Medica reveals that, whether it is the heart-qi benefit of Chizhi, the liver-qi benefit of Qingzhi, the lung-qi benefit of Baizhi, the kidney-qi benefit of Heizhi, the spleen-qi benefit of Huangzhi, or the essence-qi benefit of Zizhi, all these effects can be encompassed within the functions of Chizhi (G. lucidum).

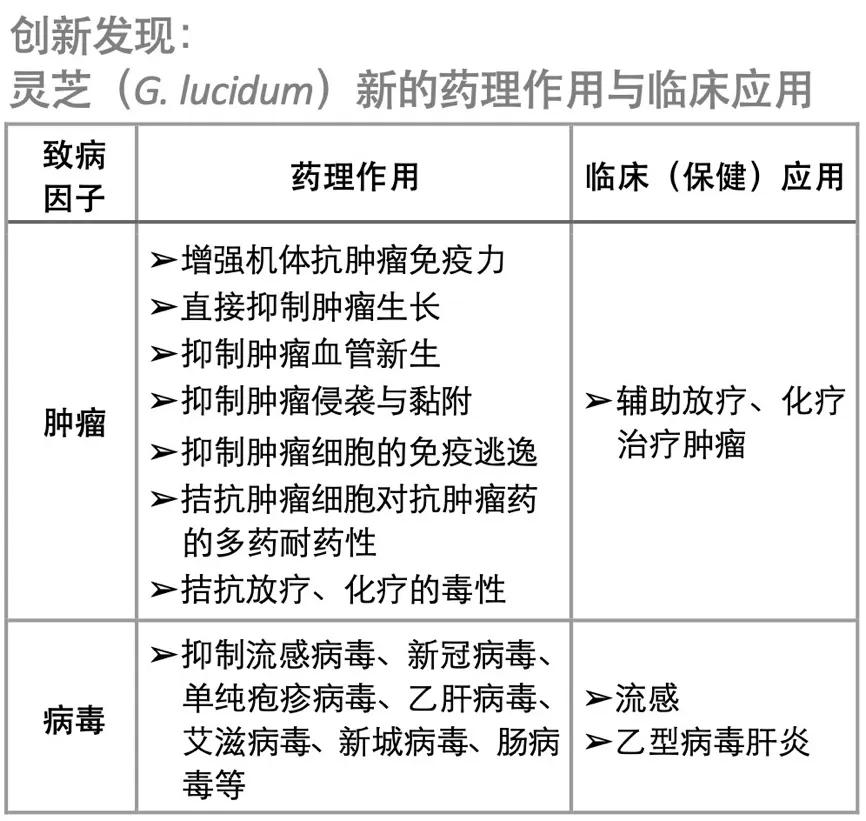

Furthermore, modern science has demonstrated that G. lucidum exhibits anti-aging effects through its ability to regulate immune function, enhance antioxidant capacity, improve learning and memory, and delay skin aging. This aligns with the Shennong Materia Medica‘s assertion that the “Six Zhis” can lead to “lightness, agelessness, and longevity if consumed prolongedly.” Additionally, modern research has revealed that G. lucidum possesses antiviral and antitumor properties, as well as the ability to enhance the efficacy and reduce the toxicity of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, representing entirely new content beyond what is discussed in the Shennong Materia Medica [5].

G. lucidum enhances qi and promotes longevity through a “multi-target” approach to strengthening healthy Qi to eliminate pathogenic factors inside the body.

In summary, the answer to the question posed at the beginning of this article is now clear. The reason modern individuals have “forgotten” about Heizhi, Qingzhi, Baizhi, and Huangzhi, as recorded in the Shennong Materia Medica, is not only because they do not fit the modern biological definition of Reishi, but also because G. lucidum alone encompasses all the effects of the “Six Zhis” discussed in the Shennong Materia Medica.

The numerous effects of G. lucidum are related to its “multiple ingredients” and “multi-target” pharmacological actions. Its regulatory effects on the neuro-endocrine-immune systems, enhancement of antioxidant capacity in tissues and cells, ability to eliminate free radicals, protection of vital organs, and suppression of tumors and viruses all contribute to the body’s maintenance of homeostasis, reduction of the extent of homeostatic disruption, and acceleration of recovery after homeostatic disturbance [6-8].

In other words, G. lucidum achieves the effects of treating different diseases with a unified approach and enhancing qi for longevity through its actions of “strengthening healthy qi to eliminate pathogenic factors inside the body.”

Expectations and Outlook

The pharmacological research on Reishi, centered on G. lucidum, integrates traditional Chinese and Western medicine, providing a modern scientific interpretation of the Shennong Materia Medica‘s discussion of the “Six Zhis.” This research not only addresses the shortcomings in the study and application of Reishi in traditional Chinese medicine over the past two thousand years but also advances scientific research, industry development, and rational use of Reishi. As a result, Reishi has transformed from an ancient miraculous herb into a food, health supplement, and medicine for modern individuals, enhancing health and preventing and treating diseases in everyday life.

Unlike ancient times when Reishi could only be foraged in the wild, with quantity and quality being unstable, modern cultivation techniques—particularly proprietary cultivation and industrial farming—provide a stable supply of high-quality Reishi raw materials. This allows companies to cater to the diverse needs of different consumer groups, producing “health-promoting” general foods, health supplements that “prevent diseases”, and medicines that “cure existing diseases”.

Although Reishi products are categorized into foods, health supplements, and medicines, they essentially retain the properties of “medicines.” This means that different active ingredients (such as polysaccharides, triterpenes, sterols and small molecule proteins) provide varying effects. Therefore, regardless of the type of Reishi product a company produces, it should establish quality standards from raw materials to intermediate products and final products, ensuring that each batch contains the types and quantities of active ingredients related to their efficacy. This is essential for truly helping consumers strengthen their health and prevent or treat diseases.

We hope that the Reishi industry can further promote the establishment and implementation of quality standards. However, current research on Reishi still tends to focus too heavily on basic science and academic theory, lacking practical application. Therefore, we look forward to collaboration between the industry and academia to conduct more clinical studies on Reishi, employing clinical trial designs that meet international standards. This will help scientifically demonstrate the effectiveness of Reishi products, ensuring that they can exert clear effects in the complex human body, rather than being regarded as placebos.

Over the past 50 years, thanks to the efforts of many individuals in the Reishi community, Reishi has emerged from its ancient myths into modern science and into people’s daily lives. Therefore, the future of the Reishi industry lies not in vague and ambiguous concepts, but in clearly defined Reishi products that specify strains, ingredients, effects, and target populations.

How can we ensure the continuous growth of academic research, product development, and disease prevention and treatment applications for Reishi? Let us encourage all members of the Reishi community to “scientifically research Reishi, apply Reishi reasonably, and evaluate Reishi correctly”!

(Photograph by Wu Tingyao)

References

1. Li Shizhen. Compendium of Materia Medica. Commercial Press, reprinted with the Shuyetang edition in the 49th year of the Qianlong reign (1784).

2. Zhao Jiding. Preliminary Investigation of the Record of Six Zhi in Ancient Chinese Texts. Microbiology Bulletin, 1989, 16(3): 180-181.

3. Wang Dequn. Exploring the Shennong Materia Medica. People’s Health Publishing House, 2023.

4. National Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China: Volume 1. China Medical Science Press, 2020.

5. Lin Zhibin. Modern Research on Reishi. Peking University Medical Press, 2015.

6. Cong Zheng, Lin Zhibin. Research on Reishi and Discussion on the Principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine for Strengthening Healthy Qi. Journal of Beijing Medical College, 1981, 13(1): 6-10.

7. Lin Zhibin. Guidance of Traditional Theories in TCM on the Research of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine of Reishi. Chinese Journal of Integrative Traditional and Western Medicine, 2001, 21(12): 883-884.

8. Lin Zhibin. Interpretation of the Healthy Qi-Strengthening Effects of Reishi through Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Research. Journal of Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2010, 20(6): 1-2, 6.

Profile of Professor Lin Zhibin

Professor Lin Zhibin has devoted over half a century to Reishi research, becoming a pioneer in this field in China. He served as the former Vice President of Beijing Medical University, the Associate Dean of the School of Basic Medicine, and the Director of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, as well as the Chairman of the Department of Pharmacology. He is currently a professor in the Department of Pharmacology at Peking University’s School of Basic Medicine. He was a visiting scholar at the WHO Traditional Medicine Research Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago from 1983 to 1984, a visiting professor at the University of Hong Kong from 2000 to 2002, and has been an honorary professor at the Perm State Pharmaceutical Academy in Russia since 2006.

He employs an integrative approach that combines traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and Western medicine to study the pharmacological effects and mechanisms of action of Reishi and its active ingredients, having published over one hundred research papers on the subject. He is the author of several notable works, including Modern Research on Reishi, Lingzhi From Mystery to Science, Reishi for Strengthening Healthy Qi to Eliminate Pathogens and Auxiliary Treatment of Tumors, Discussions on Reishi, Pharmacology and Clinical Applications of Reishi, Ganoderma and Health, and Reishi and Tumor Prevention and Treatment.

In 2020, he was selected as one of the “World’s Top 2% Scientists” in the category of “Lifetime Scientific Impact (1960–2019)” by Stanford University and Elsevier Science.